- Polyweb

- Posts

- How to set OKR from scratch

How to set OKR from scratch

In which we talk about how you can set OKR for your team step-by-step, how to avoid common pitfalls, differentiating between key results, KPI and task, and we make some concrete examples along the way

✨ Hi, I’m Sara Tortoli and this is the March edition of The Plunge Club, a monthly newsletter dedicated to product and human tinkering.

If you are not a subscriber yet, then you are welcome to take the Plunge and join the Club:

Last week I gave a talk at the Product Led Alliance Festival on my experience in setting OKR from scratch. In this issue I am sharing the major points of the keynote and I answer in further detail some of the questions and requests that came from the people that attended the event.

How it started with OKR

I heard of OKR and saw them implemented for the first time back when I was working at Zalando. To be honest, I thought little of them at the beginning. I was under the misconception that OKR were only a fancy way to disguise KPI (more on the difference between the two below). It was only after seeing them in action for a while, that I changed my mind. I began to appreciate OKR at first through self-experimentation, by implementing them in my personal life (if you are curious about how I did it, I wrote about it in “How to productize yourself”). This gave me a good understanding of what worked and what didn't, as I had plenty of "skin in the game". Later on, this proved to be extremely useful. I started setting up OKR from scratch at first in my team, and then helped others do the same. Through my own mistakes and that of other teams, I started figuring out a formula to successfully set OKR from scratches. This step-by-step guide is a collection of what I have learned thus far.

What is an OKR?

OKR stands for objective and key results. They became popular when John Doerr introduced them at Google and since then they have spread pretty much in every tech company. To know more, I recommend watching this TedTalk from John Doerr.

OKR are beneficial in aligning an organization behind a shared purpose and in breaking down a vision around well-defined business objectives. When implemented correctly, they promote a sense of ownership within teams. What I like best about OKR, is the push to be daring and to accept that failure is a natural component when trying to achieve big dreams. After all, the whole point is: “Shoot for the Moon. Even if you miss, you will land upon the stars”. Turns out, however, that even if this sounds simple and very compelling in theory, implementation is actually difficult.

Enter the pitfalls

OKR might be counterproductive when not implemented correctly. Mistakes are just around the corner and in the slide below, I have summarised eight of the most common pitfalls.

So how can we set OKRs from scratch that are effective? In the next section, we examine best practices and how we can set OKR step-by-step so that you can reap all the benefits and avoid the eight most common pitfalls.

Setting OKR from scratch step-by-step

Step 1: Start with the end goal in mind

This is the most important, and the most neglected element at the same time. Often teams jump to write objectives without a long-term plan, only looking at what is in front of them at the moment.

To set OKR that are effective, you need to start from a vision, or at the very least, from a long-term strategy. You need to know your end game, what you want and why, for OKR to work.

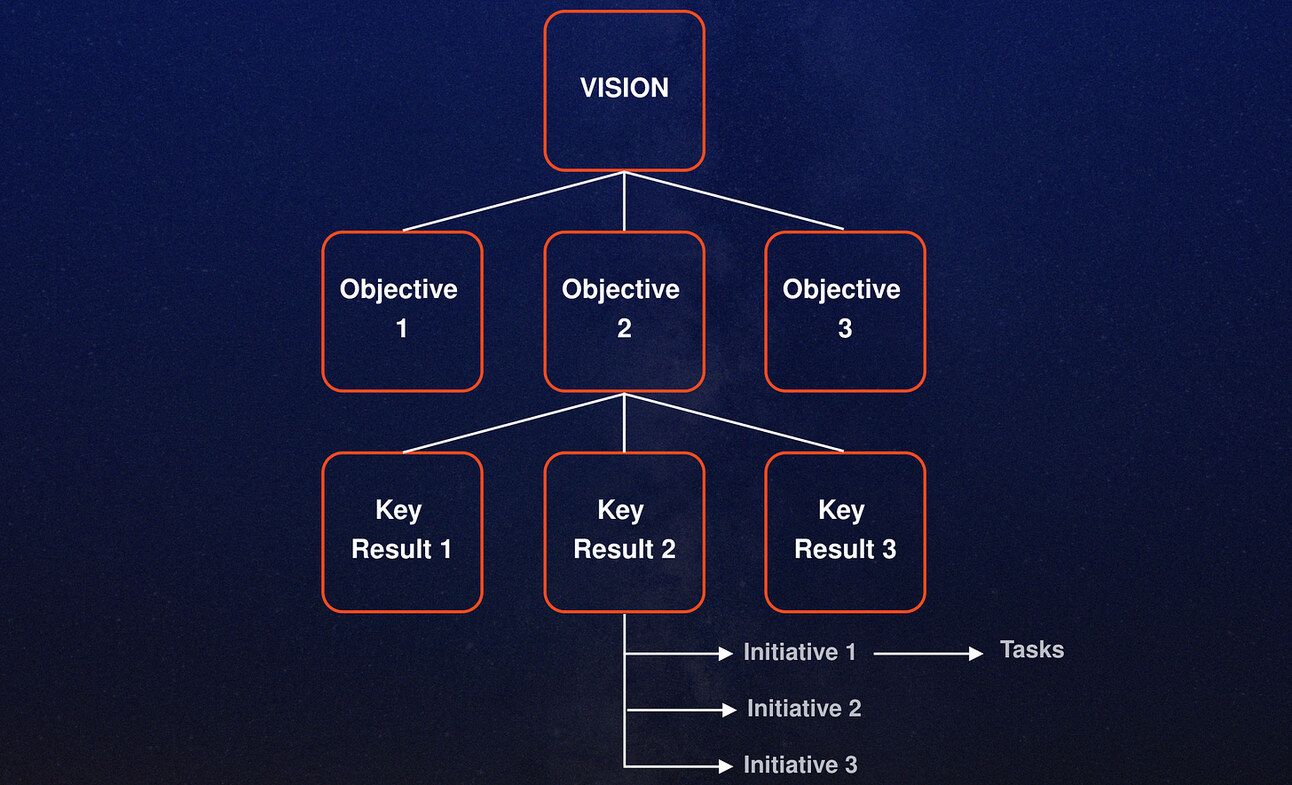

So the first step when setting OKR is to write a vision statement of your company AND of your product. The vision needs to include a long-term strategy of at least 2 years, and this will be the background to form your objectives. I have illustrated the hierarchy and connection among the different elements in this picture:

Step 2: who sets the OKR? Enter the team

This question might seem trivial, but it actually isn’t. In companies, often the OKR are set by the various leads. The teams that have the responsibility to fulfill the OKR have little to no say in their setting.

When this is the case, it takes away the sense of shared ownership and the team becomes a mere executioner. Also, you will take away the creative ability of the team to deliver value. The team is much closer to the end-users than the lead usually is, so they are in a better position to foresee what would get meaningful results.

Setting OKR with the team is actually a great way to boost team spirit. The work of the lead is that to empower the team to make the best possible decision. This includes bringing all the facts, presenting business priorities, and sending pre-reads before the session. Afterwards, it means aligning with stakeholders and other teams to finalize OKR.

If you are wondering who in the team should be involved, the answer is everyone. For example, if you are a product manager and you are setting OKR for your product, you will involve developers, designers, data scientists, and so forth. In general, you involve all the roles and people that actually build or are responsible for your product.

Step 3: OKR planning session

The best way to illustrate a planning session is actually with a concrete example. Below I attached a screenshot of the Miro board I use in the planning sessions with my team. I like to turn the planning of the upcoming OKR into a quarterly team event. We start in the morning by running a retrospective, before jumping into the planning session itself in the afternoon. Before setting OKR, we go over:

Product vision: everyone re-reads the document and can make suggestions on what we can do this quarter that will get us closer to its fulfillment

OKR of the previous quarter: to see what we achieved and what we missed and still need to work on

Business priorities: what are the needs coming from within the business and from our users

Company and/or department OKR

In the “topics” area of the Miro board, we have two elements. In the “committed” items, we write things we need to do that are already committed by the business and/or by other teams. An example of a committed item is the company OKR that “cascade” to the team. The “proposed” items, come from suggestions within the team itself. They are things we would like to do and that we think will bring value to the product and to the business. We then discuss the various options and what among the “proposed” items can be done along with the “committed” ones.

Our goal by the end of the session is to have a completed proposal of OKR, clearly stated, along with some initiatives.

Step 3: Writing the OKR the right way and how to distinguish Key Results from KPI and tasks

This brings us to the third step, which requires paying attention to the form and the content of the OKR, namely what you write and how you write it.

Objectives by definition should be moonshots. They should make you feel uncomfortable and inspire you at the same, pushing you to dare. Objectives are the breakdown of the vision, this is where their aspirational attribute comes from.

Key Results (KR for short) are measurable, and unlike objectives that can have a qualitative nature, they need to be specific and quantifiable. They have to contain either a number, a date, or have a binary nature (yes/no). If you cannot answer for sure if you have achieved a key result or not, and you can debate with someone over their fulfillment, then they have not been written properly. To the question: “have you achieved your KR?” the answer needs to be a self-evident yes or no, no wiggle room.

The most common pitfall when setting key results is writing them as tasks or confuse them with KPI. Let’s distinguish between them and make a concrete example.

Key results vs. tasks: key results are outcomes you want to achieve that will allow you to fulfill your objective. To help you do that, you can break down key results into tasks, step-by-step action items. When your objective is not big or aspirational enough and/or is not tied to a vision, you risk writing tasks instead of KR. One useful way to distinguish between the two is to ask yourself: “If I close these key results, will I have fulfilled my objective?”. If the answer is no, then you have probably written tasks instead of key results.

For example, if you want to increase awareness around your product as an objective, writing as a KR “running 1000 ads” will not automatically guarantee you will achieve the objective. We can easily ignore ads, hence this is might be a potential task in pursuing your objective, but not a key result. A better way to formulate the KR would be, “increase sign up by x%”, and you could achieve that by creating many initiatives, running ads being just one of them.

Key Results vs. KPI: as both key results and KPI have a measurable and quantifiable nature, it is very easy to swap the two. Key results are specific and tied to the objective and the vision behind it. They have a much broader nature than KPI, which instead measure the progress of your product. Can a KPI be key result? It depends on the objective. If you think one or more KPI are core outcomes to achieve the objective, then you can pick some as your KR. Again ask yourself: “If I close these key results, will I have fulfilled my objective?”. Let’s make a concrete example with this newsletter. Starting from the vision, I will break it down into OKR, KPI, and tasks.

OKR vs. KPI vs. Task Example: The Plunge Club

Note that, for example, I could have put as a key result: "Reach 5000 subscribers" instead of having # of subscribers as a KPI. The reason I didn't is that reaching a random number of subscribers doesn't mean I will be closer to the vision of meaningfully interacting with people. Hence, it is better as KPI than a KR. Conversely the first KR, “learn 1 topic every month” could very well have been a task. However learning new things is the only way to deliver more value and to become a world-class newsletter. It’s also one of the principal purposes of why I write the Plunge Club and much more meaningful than a simple item in a to-do-list, therefore it is a KR rather than a task.

Step 4: execute

Now that you have written your OKR, it’s time to execute. This means you need to break down your key results into initiatives. Initiatives are projects or milestones you need to achieve in the pursuit of your KR. Initiatives are further broken down into tasks.

To increase accountability around OKR, I organize the team into “squads” for each KR. Each “squad” has all the competency needed to fulfill the KR and works like a self-autonomous sub-group. An individual team member is assigned to one or more KR.

Step 4: the review process

Another consistent pitfall to be wary of is setting up OKR once and then don’t look at them again until the end of the quarter/year. When this happens, you are treating OKR like the magic wand, expecting that they will turn a "pumpkin into a coach" on their own. However, OKR are a tool and like any other tool, they need work and supervision. This means you need to review them frequently, to adjust the route along the way if you are still too far from the mark. A good practice is to have checkpoints (e.g. monthly), or at the end of every building cycle (e.g. sprints), and to write the progress made.

Example: OKR as a product manager

Let’s say that you are a product manager for a marketplace that is selling house appliances. The marketplace has launched a few years ago, and although it is still young, it has already reached a loyal customer base. Lately, however, you have not been growing at the same fast pace as the previous years and you feel you are not innovating enough. In short, you are missing the WOW factor, and on your vision of surprising customers with new features and deals. So you write an objective to achieve this: WOW our customers. The OKR for a product team will look something like this:

The team measures the achievement of the objective by writing 3 key results. The first one is a bet: the team wants to push for innovation, so it chooses to launch a new feature and will determine if that bet has paid off by the number of new customers it will attract. Furthermore, the team thinks that an increase in the number of sign-ups and NPS will be a good proxy to understand if there is a WOW effect on the customers. Note that #of sign-up and NPS score are likely also KPI of the product. The team still chooses them because they are a good signal for the objective.

Now the team knows the answer to the question “when are we successful?” but does not know how to reach those numbers yet. Therefore they will start brainstorming ideas, writing initiatives. The most promising of those initiatives, the one the team is betting on, will be turned into epics and will enter the backlog. We can tie each epic to one or more KR. The more KRs a single epic fulfill, the more valuable this epic becomes, helping you prioritize.

The team members will also start assigning themselves to specific KR, operating as a sub-team or squad (see step 4). You also write dependencies on other departments to fulfill your objectives, ensuring their support in their respective OKR.

Finally, as the team starts developing, you track progress. Assuming the team works in sprints, you grade results at the end of each sprint, prioritizing and allocating resources differently depending on what still needs to be done.

What about your experience with OKR? Share and let me know if you have any question by hitting me on Twitter or on LinkedIn

The “Now” section

🎧 What I am listening to: Brian Chesky, CEO and founder of Airbnb, talking about the “rebirth” of the company in this episode of Master of Scale. From the layoff during COVID, to the IPO last summer, it’s an intense story of “going back to the roots”. Chesky says that in a crisis, we need to make decisions based on principles, rather than business logics. You cannot predict the outcome of a crisis, so better ask yourself: “if all is lost, how would we want to be remembered?”.

📚 What I am reading: Antifragile by Nassim Nicholas Taleb and I didn’t get it. In fact, I read about 200 pages (it’s over 600 total) before giving up and reading this book summary. I actually found the concept and some reflections in the book interesting. The idea is that our world benefits from short-term and frequent shocks, as opposed to big but infrequent ones, as a way to make us “antifragile” and I also appreciated the examples and parallels. What put me off is the style and the tone in which the book is written and the fact that I don’t believe it takes 600 pages to express the concept.

🥁 What I am doing: I am learning about crypto and Defi. I started falling into this rabbit hole and I keep digging around, building my knowledge and understanding from the ground up. In fact, I will share my learning soon. Which question would you like me to answer regarding the crypto space?

🧐 Question I am asking myself:

We spend all our lives with a constant companion, an internal voice that never leaves us alone. But how are we talking to ourselves? Are we thinking of ourselves with kindness or are we our harshest critique, looking to constantly criticizing ourselves? By asking myself this question, I am trying to become aware of how I am talking to myself to become kinder and more accepting.

✨ If you like this newsletter and found the content useful, please consider sharing it with other people who are ready to take the Plunge and join the Club: